- Home

- Thomas Flanagan

The Year of the French

The Year of the French Read online

THOMAS FLANAGAN (1923–2002), the grandson of Irish immigrants, grew up in Greenwich, Connecticut, where he ran the school newspaper with his friend Truman Capote. Flanagan attended Amherst College (with a two-year hiatus to serve in the Pacific Fleet) and earned his Ph.D. from Columbia University, where he studied under Lionel Trilling while also writing stories for Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine. In 1959, he published an important scholarly work, The Irish Novelists, 1800 to 1850, and the next year he moved to Berkeley, where he was to teach English and Irish literature at the University of California for many years. In 1978 he took up a post at the State University of New York at Stonybrook, from which he retired in 1996. Flanagan and his wife Jean made annual trips to Ireland, where he struck up friendships with many writers, including Benedict Kiely and Seamus Heaney, whom he in turn helped bring to the United States. His intimate knowledge of Ireland's history and literature also helped to inspire his trilogy of historical novels, starting with The Year of the French (1979, winner of the National Critics' Circle award for fiction) and continuing with The Tenants of Time (1988) and The End of the Hunt (1994).

Flanagan was a frequent contributor to many publications, including The New York Review of Books, The New York Times, and The Kenyon Review. A collection of his essays, There You Are: Writing on Irish and American Literature and History, is also published by New York Review Books.

SEAMUS DEANE, formerly Professor of English and American Literature at University College, Dublin, is now Keough Professor of Irish Studies at the University of Notre Dame. Among his books are Selected Poems, Celtic Revivals, Strange Country: Ireland and Modernity, and the novel Reading in the Dark. He was General Editor of the three-volume Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing.

THE YEAR OF THE FRENCH

THOMAS FLANAGAN

Introduction by

SEAMUS DEANE

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

This is a New York Review Book

Published by The New York Review of Books

435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

Copyright © 1979 by Thomas Flanagan

Introduction copyright © 2005 by Seamus Deane

All rights reserved.

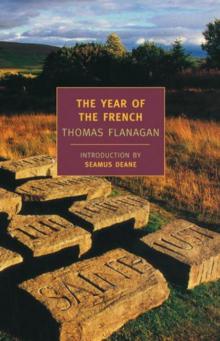

Cover image: Ian Hamilton Finlay, The Present Order Is the Disorder of the Future, Saint-Just, from the garden at Little Sparta; courtesy of the artist and Victoria Miro Gallery, London.

Cover design: Katy Homans

The Library of Congress has cataloged the earlier printing as follows:

Flanagan, Thomas, 1923–

The year of the French / Thomas Flanagan ; introduction by Seamus Deane.

p. cm. — (New York Review Books classics)

ISBN 1-59017-108-X (trade pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Ireland—History—Rebellion of 1798—Fiction. 2. French expedition to Ireland, 1796–1797—Fiction. I. Title. II. Series.

PS3556.L3445Y43 2004

813'.54—dc22

2004017965

ebook ISBN: 978-1-59017-686-3

v1.0

For a complete list of books in the NYRB Classics series, visit www.nyrb.com or write to:

Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

Contents

Biographical Notes

Title Page

Copyright and More Informaction

Introduction

THE YEAR OF THE FRENCH

Dedication

Prologue

Part One

1

2

3

4

5

6

Part Two

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

Part Three

18

19

20

21

22

Epilogue

Winter, 1798

Principal Characters

Maps

Introduction

One morning in the spring of 1978, I was clearing my mailbox in the faculty office of the English Department in Wheeler Hall at the University of California at Berkeley, when I noticed that Tom Flanagan’s ears had risen a notch or two along the sides of his perfectly bald head. His mailbox was close to mine and he had his back to me, but it was evident from the ears that he was smiling—no, that he was beaming. I stepped over and said to him, “So, what’s the good news?” He was holding an opened letter across his chest and said to me, “Just the biggest check I’ve ever seen; or the biggest one made out to me anyway.” But he would not go further, although I later learned it was his advance for The Year of the French.

That was the beginning of the great adventure of The Year of the French; it became a best-seller in the US, and also sold very well in Ireland. In Ireland, too, it had a remarkable second life after the national television company, Radio Telefis Eireann (RTE), decided, in collaboration with the French television channel FR3 and the British Channel 4, to make it into a film that was broadcast on television in late 1982 in a six-part series.

This was by no means an unmixed blessing. Flanagan’s friend Conor Cruise O’Brien, then editor of the London Sunday newspaper The Observer, reviewed the novel very favorably. O’Brien had previously been a government minister in charge of broadcasting in Ireland and he exerted his considerable influence to persuade RTE to invest a large sum of money (eventually 1.7 million pounds sterling) in the venture. The film presented the novel as a tract against violent rebellion, even against an unjust established order, and further suggested that rebellion was an ingrained and reactionary habit of the Irish that provoked British occupying forces to commit yet another series of their periodic atrocities in the name of law and order. O’Brien and many other influential people in the media were then on the crest of a crusading wave against Irish republicanism, especially its military operations in Northern Ireland.

It cannot be said that this production did the reputation of the novel any good, even though it was lavishly done, had a great musical score (by Paddy Moloney of the Chieftains), and caused great local excitement in the forty locations in County Mayo where it was shot. It was not entirely a travesty of the novel, but it was not a treatment that was anxious to preserve the nuances of Flanagan’s text. Yet in another sense, the film helped turn the novel into a phenomenon. Local people in County Mayo especially began to refresh their views and their inherited memories of the Great Rebellion of 1798 in Ireland, the ferocious and bloody prequel to the Act of Union between Great Britain and Ireland in 1800, that created what is now known as the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Most of the ferocity was displayed by the regiments of the British army, who killed 30,000 people in a few months, making the slaughter in revolutionary France earlier in the decade seem quite tame in comparison.

Ireland at that time was a profoundly sectarian state in which the bulk of the Catholic population was allowed no political existence and a Protestant minority, notorious for its unflinching bigotry—what Edmund Burke called “a plebeian oligarchy” that had begun to style itself in the decade of the rebellion as an “Ascendancy”—sought tirelessly and cynically to preserve its own contrastingly privileged position. The United Irishmen, who led the rebellion, posed a lethal threat to this rancid system; its leadership, largely Presbyterian and predominantly from the North of Ireland, promoted a secular dream of Irish separation from England and an end to the injustices and divisions upon which that relationship’s security depended. The leader of the United Irishmen, Wolfe Tone, sought help from the French government

, which had already abandoned its radical revolutionary phase and entered upon the period of the Directory and the subsequent Napoleonic military dictatorship. Twice the French attempted to land an army in Ireland: once in 1797 at Bantry Bay, off the Kerry coast, a venture defeated by bad weather, and the second time at Killala in County Mayo in 1798, after the main rebellion, which had broken out in County Wexford, had been defeated.

Those who opposed the rebellion and wrote its history claimed that it was nothing more than a sectarian Catholic assault on the local Protestants, of the kind which their propaganda had been telling them for two centuries to expect. The Catholic peasantry had their own elaborate political views, mostly Jacobite rather than Jacobin, favoring the deposed Stuart monarchy and opposed to the Glorious Revolution of 1688 that had brought a triumphalist Protestantism and the infamous penal laws against Catholics in its train. They rose in rebellion largely because of provocation by government forces in 1797 and also in reaction to the various oppressions they endured. Yet in the conventional accounts of the rebellion, they were depicted as a purblind community, far removed from any enlightenment or revolutionary ideals; and their secular leaders as irresponsible intellectuals who had led astray a benighted peasantry.

The arguments created by Flanagan’s novel were largely concerned with its complicated narrative techniques, the success of these in rendering some sense of the political complexity of the situation, and the pertinence of the work to the contemporary political crisis in Northern Ireland in particular. For some historians it was too “literary” to be wholly reliable; for some literary people, the literary skills were precisely what gave the work an imaginative and sympathetic dimension that any polemical political reading of the novel was obliged to ignore. But the film version produced another, quite different, reaction. It led to a widespread renewal, at first in County Mayo and later elsewhere, of interest in the microhistories of the various localities mentioned in the novel and included in the shooting of the film—sometimes indeed because a site mentioned in the novel, like the site of the final and fatal battle of Ballinamuck, had not been used in the making of the film. Also, the various personages mentioned in the novel gained a new prominence, among them the French General Humbert, after whom a summer school is now named. (Summer schools, which can last from a couple of days to two weeks, are now pandemic in Ireland. Flanagan’s novel played an important role in stimulating this relatively benign development.) It is appropriate too that this novel should have had such a visible influence, visible even in the most literal sense, by helping to make the areas around Killala and Ballina tourist attractions. Road signs bearing the book’s title, The Year of the French, appeared, although they were, in the traditional way, carefully and obliquely angled to create confusion rather than clarity in the mind of the traveler caught in the network of spidery roads that lay across the wild and desolate landscape that is such a persistent presence in the book.

Thomas Flanagan had altered the Irish literary landscape once before in his marvelous study The Irish Novelists, 1800–1850, published by Columbia University Press in 1959. This book still has no equal for the wit and penetration, the learning and the sympathy, that it brings to bear upon writers like the Banim brothers, Gerard Griffin, William Carleton, and many others who disappeared from view in the retrospective blaze of Joyce’s reputation, like stars in sunlight. Part of the appeal of this book is that it shows not only a wide knowledge of the novels themselves, but also a knowledge of what the novelists had read. Thomas Flanagan’s range of reading was immense; every page of The Year of the French bears the imprint of this. Quotations from Irish (often in well-known translations or adaptations) and from English and French are embedded in his prose, and yet they are so easily lofted into his narrative that they bring no burden to bear upon the reader. The style is literary in the best sense, for this novel aims to provide that thickness and richness of detail that a great historical novel needs, yet is also determined to avoid simply dressing the story up as a costume drama.

But it is not enough to speak only of one style, although there is indeed, throughout the whole book, the indelible mark of a sensibility. There are different styles adapted for each of the five major narrators. The success of this polyphonic structure of voices is underwritten by Flanagan’s great and appreciative knowledge of the masters of nineteenth-century fiction, Irish, English, American, and French. There are also subtly flexed variations on social and historical types. We know from the work of Scott and Edgeworth and from later critical writings by Manzoni and Lukacs that the stereotype is unavoidable in historical fiction, since in it the individual person must always serve at least to some extent as a representative of a community. The danger of course is that the stereotype may turn out to be crude and destructive. In the case of Ireland and Irish writing, there is immense temptation in this regard, since its colonial history has made the stereotyping of “native” character so easy and vulgar an attraction. The author who succumbs to the temptation presents a cartoon “realism” that impedes the possibility of analysis.

Perhaps it is in the figure of the poet-schoolmaster Owen Ruagh McCarthy that Flanagan most obviously takes up the challenge of the stereotype and the struggle to overcome it without entirely abandoning the useful narrative functions it can command. If one reads some of the memoirs of Gaelic poets of the eighteenth century or even looks at some of the most famous representations of the histrionically doomed Irish poet, victim to drink, drugs, and history, like Joyce’s representation of the poet James Clarence Mangan, who died of cholera during the Famine, then one can see some of the sources for Flanagan’s Owen McCarthy. Other sources lie in the realm of folk memory.

But not many. This is a historical novel in a profoundly literary sense; it draws on printed and written sources, but rarely looks to folklore. This makes it the more choice that the novel could legitimately be said to have given a great impetus to the revival of folklore accounts and memories of what the local people have always called Bliain na bhFranchach (“the year of the French”). The film of the novel is certainly central to this aspect of its influence. But it is also a tribute to the novel’s capacity to endure such a transient and polemical adaptation and thereby reveal its richer resource. It was the fact that this novel came from outside Ireland and that it delved into such detail about the local area that, for many local historians, increased the prestige of the local memories and revived that prestige in time for the bicentenary of the invasion in 1998.

So here we have a great historical novel created by a great literary scholar and raconteur, that has already been incorporated deeply into the contested literary and cultural history of modern Ireland. It helped to bring into focus within one concentrated sequence the calamitous history of a century and a country when Ireland was invaded by the French for one month in the late summer of 1798. The history of its own reception since its first publication in 1979 is by now part of the history of the reception and interpretation of 1798 itself.

—SEAMUS DEANE

THE YEAR OF THE FRENCH

For Jean, as always,

and for Ellen and Kate.

In memory, as always,

of Ellen Treacy of Fermanagh

and Thomas Bonner of the Fenian Brotherhood.

PROLOGUE

Early Summer, 1798

MacCarthy was light-headed that night when he set out from Judy Conlon’s cabin in the Acres of Killala. Not drunk at all, but light-headed. He carried with him an inch or two of whiskey, tight-corked in a flask of green glass, and the image which had badgered him for a week. Moonlight falling on a hard, flat surface, scythe or sword or stone or spade. It was not an image from which a poem would unwind itself, but it could be hung as a glittering, appropriate ornament upon a poem already shaped. Problems of the craft.

Halfway to Kilcummin strand, the sullen bay hammered flat to his right, and to his left a low stone fence, he took the flask from a back pocket of his long-tailed coat. Within the coloured glass, in

the clear light of summer’s evening, the whiskey was a drowned moon. When the flask was empty, he sent it on a high arc towards the shore. Like moonlight’s glint upon water. Or its glow upon her rounded breast. No, the image demanded a flat surface. Until he had the image, he would be its slave.

At Matthew Quigley’s tavern, a long, low cabin across the narrow road from the rock-strewn strand, he put his fist to the door, knocked, and waited. Quigley opened it for him, a short, bandy-legged man, bald, with a large head round as the full moon.

“You are late,” he said.

“I am,” MacCarthy said. “I had better things to do.”

“You did to be sure,” Quigley said. “In the Killala Acres.”

“It is where I live,” MacCarthy said. Quigley stood back, and he entered the tavern, bending his neck to the low door. He was a clumsily built man, tall and raw-boned, with long arms reaching towards his knees from heavy, sloping shoulders. It was a ploughboy’s body, and a ploughboy’s head, thatch of coarse red hair like a beacon fire on a hill, long, thin lip.

Three men sitting by the cold fireplace looked up towards him, and one of them spoke. Malachi Duggan, a heavy bull, shoulders hunched forward. “You are late.”

“So it would seem,” MacCarthy said. “I don’t own a watch.”

But he did. A handsome gold watch as thick as a turnip, given him years before by some gentlemen of North Kerry after a poetry competition, with branches and sprays of flowers traced upon its casing. Useless now, smashed one night in Newcastle West, the casing bent, and a litter of cogs, wheels, and springs beneath the splintered white dial, a shattered moon.

“You will take a drop,” Quigley said, and filled a glass for him.

“He has never been known to refuse one,” Phelim O’Carroll said. “Have you, Owen?”

The Year of the French

The Year of the French